Smoke riseth out the chimmuck.

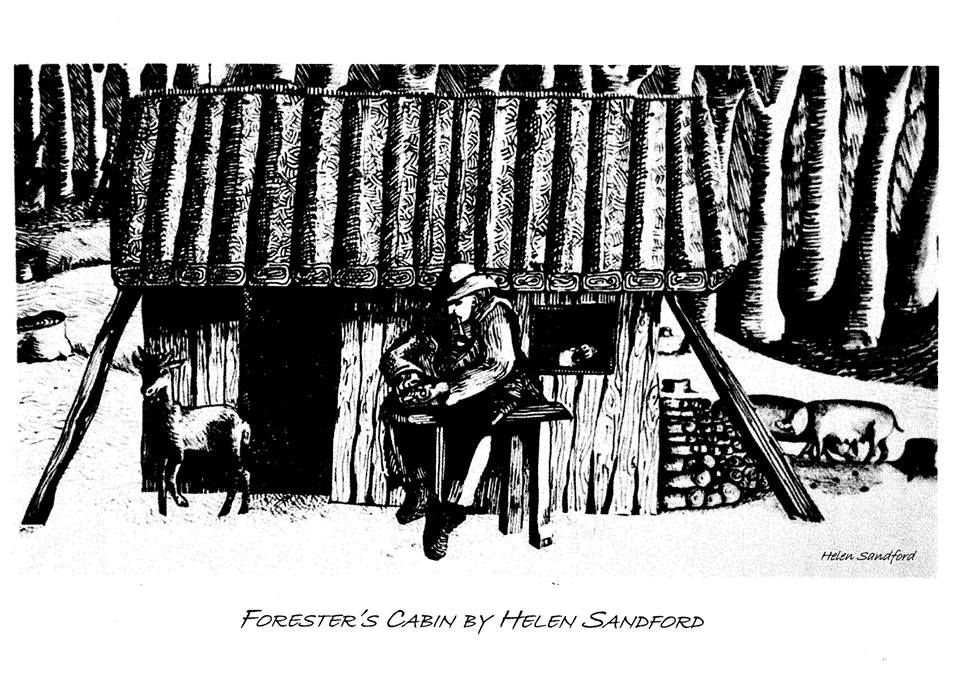

The turf-covered cabin, resting on four dry walls, with a fireplace & chimney in "the pine end", was once the habitation of the Forest Cabiner. In bygone days, if a few neighbours accomplished the erection of a cabin and set therein a fire before morning dawned, no-one had power to pull it down.

History and Mythology

"Tyme out of Mynde"

Our ancestral Foresters have settled and maintained their (often completely illegal) occupancy of the Forest of Dean, for time out of mind, resisting monarchs and governments who ethnically cleansed the so-called 'disorderly settlements' which characterised so much of the Forest's natural, industrial and cultural heritage.

Our ancestral Foresters have settled and maintained their (often completely illegal) occupancy of the Forest of Dean, for time out of mind, resisting monarchs and governments who ethnically cleansed the so-called 'disorderly settlements' which characterised so much of the Forest's natural, industrial and cultural heritage.

It is said that every single town, village and hamlet in the Dean began as an illegal squatter settlement. Of course they were only seen as illegal by them lot in London -to the Foresters, they were our homes, and building our own low-impact cabins and living a self-sufficient 'good life' is the indigenous way of life here in the Forest. At various times throughout the centuries, foreign criminals with support from the political class employed mercenaries to ransack our communities. They burnt Forest families out of house and home, selling large portions of our beloved Forest to their friends in London to pay the mercenaries.

The Dean Forest Clearances were unique, at no one time did they affect as many people as the Scottish Highland Clearances, but they were no less violent and happened again and again over many centuries. Throughout this time and in order to justify the land grabbing and violent evictions, rebellious Foresters were called many derogatory names: encroachers, squatters, poachers, trespassers and most accurately 'cabiners'. Despite this long and traumatic history, or maybe because of it, Foresters remained...

The last of the Cabiners were evicted, their homes destroyed on Ruardean Hill or possibly The Pludds in the first part of the twentieth century. Many of our smallholdings, fruit orchards and cottages which began as 'illegal *encroachments' and 'squatter settlements' were abandoned at around this time. Some were taken via 'adverse possession' and incorporated into the estates of larger landowners; others defaulted to the Crown -their true owners lost in the industrial-scale slaughter of the wars in Europe. Our oral history certainly places the last of the Cabiners as living on the hills of Ruardean around this period. They would have grown their own food, kept animals in the forest (likely pigs and sheep) and perhaps made a small living from woodland crafts.

Ecology and the Ethnosphere

Our Forest has always been an ecologically wealthy and highly productive area, more than capable of feeding its own population. Warm air comes up the Severn and is channelled through our many wooded valleys, making the Forest an ideal micro-climate. The area has been famous at various times throughout the centuries for its productive wealth of orchards, small farms and abundant game. When our lands were well managed, there was no need for anyone to go hungry.

By all accounts, when Forest communities were left in peace to work on the land (and under it) they were not just self-sufficient but actually thrived! Gardens were well kept, sheep grazed under our mighty Oaks and orchards provided cider apples and many other kinds of fruit. The Dean has produced several well-known and many obscure varieties of apples, pears and plums over the centuries. This is testament to the time, skill and dedication that Foresters gave to the task of improving their local crop varieties.

Self-sufficient homes produce independent-minded folks who tend to form strong and independent communities with their neighbours and extended families. This helps to forge a spirit of co-operation and builds strong local economies by cycling resources and opportunities within the community. Producer-led markets & supply networks reduce dependency on imports from unstable global markets and instead invest in local industries.

These is good evidence for a 'functional connection' between local cultures, languages and biodiversity. The areas of the Earth where regionally adapted ‘local’ cultures flourish, tend to be the areas where the biodiversity of the natural world still thrives. A recent study found that 70% of the world's languages are found within the planet's biodiversity hotspots. Out of 6,900 or more languages spoken on Earth, more than 4,800 occurred in regions containing high biodiversity. The ethnosphere, with its cultural adaptations to place, works to either sustain or destroy the Earth's biodiversity.

A brief history of the Forest.

Before the mid 19th century, almost everyone in the Forest lived in log cabins they built themselves. Foresters were self-sufficient and viciously independent. For centuries the self-proclaimed 'authorities' in London continued to view us as illegal squatters; the fact that Foresters have lived in the Dean since -at least- the time of the Anglo-Saxon settlements (well over a thousand years ago) didn't prevent modern politicians from picking up the imperial baton from the Latin speaking French-Norman aristocrats who originally labelled us as 'savages' and accused us of squatting on our own land.

The inhabitants are, some of them, a sort of robustic wild people, that must be civilized by good discipline and government.

(The natives are) “exceedingly excitable,” and “nearly as wretched as anything now existing in Ireland”. Dr Parsons quoted around 1810.

For close to a thousand years, those families who dared live within the Forest were under constant threat of eviction. They were 'cleared' from their own lands countless times, only to defiantly return and rebuild their lives. The Forest proved a good place to hide from the authorities, being sparsely populated with terrain almost as rugged as the folk that walked upon it. Rebel forest communities also had strength in numbers -sharing fate with the other 'illegals'. For long periods in the Forest's unique history, we had what is known legally as 'de facto' independence -meaning we were self-sufficient and stood-up for ourselves, defending our communities from London's predations and attempted robbery.

Having formerly pulled down and destroyed many cottages, fences, and enclosures, he had latterly been obliged to desist, fearing his life and property were endangered by the repeated threats and insults of the *encroachers and their party. Mr. Thomas Blunt, deputy- surveyor.

*ENCROACHMENT: mid-15c., '*obtruding structure', from Old French encrochier: 'seize, hang on (to), cling (to)'.

*OBTRUDE: from Latin obtrudere "to thrust into, press upon,": ob "in front of; toward" + trudere "to thrust, push."

The Changing Forest

In the last few decades alone, there have been three attempts 1981, 1993 and 2010/ 11 to sell-off our 'public' woodlands, this would have effectively ended the customs and traditional land management systems, by which Foresters have sustained themselves since ancient times. In 1981 Member of Parliament for the Forest of Dean Paul Marland initially supported the privatisation, though he quickly realised his mistake saying...

Today’s Forester is of the same independent mind and rugged character as were his forefathers. It is our duty to preserve his ancient rights and traditions.

The Forest would be sold off over my dead body.

(Former) Member of Parliament, Paul Marland.

October, 2010 A leaked Government consultation contained a proposal to sell-off all 258,000 hectares of the Public Forestry Estate (PFE), including 22% of all ancient woodland sites in the UK. The PFE is the only large estate set-up by the Norman aristocracy which today even attempts to present itself as "public"; the PFE contains roughly the same amount of land as Britain’s 16.8 million home-owners are permitted to scrabble for. The campaign group Hands Off Our Forest was formed at Speech House -right in the center of our Forest- where more than 3000 people soon after gathered in the snow to burn a giant effigy of Big Ben. Groups rallied to action across the country to help oppose the sell-off.

One recent tragedy which undermined the ability of Foresters to be self-sufficient was the 'foot and mouth' outbreak of 2005. This crisis was ruthlessly exploited as a means to further erode the ancient customs and rights of the Commoners, who have kept sheep in the Forest for over a thousand years. The Commoner way of life was dealt a serious blow and the Forest sheep, once so common a sight as to be thought of as almost inseparable from the landscape, have yet to truly return to their ancient woodland pastures. Our unique arboreal-pastoral systems (wide-spaced trees with pasture beneath) which provided habitat for innumerable butterfly and other species, now yield to the Bracken and Brier.

1985 “The Forestry Commission’s Broadleaves’ Review and amendments to the Wildlife and Countryside Act 1985 was the first time in its history that the F.C. had a statutory duty related to 'environmental issues', this -at least in theory- marked a turning point in post-war forestry policy.

1940-50 Italian prisoners of war were used as a utilitarian army, and swept through the Forest of Dean with saws, felling tens of thousands of trees.

1900's The majority of the ancient native woodlands under the Forestry Commission’s management have been clear-felled and extensively replanted with non-native conifers. According to Professor Oliver Rackham, as much Ancient Semi-Natural Woodland was destroyed in Britain during the 30-40 years after World War Two as in the previous four hundred years.

The Poor-man's Aristocracy

Eventually, some limited residential rights were given to the Freeminers of the Dean who even though "they had been born in it, and never lived elsewhere... had to work seven years in the pits before they could become free". These rights, granted in the mid 1800's, were to change our landscape considerably. Prior to this the entire population of the Forest lived in a permanent state of resistance, building their homes in accordance with ancient customary rights which were upheld in defiance of external (foreign) authority. Without the ever present threat of eviction, Foresters began to build more stone cottages rather than their traditional log-cabins. This created what has been called a 'poor-man's aristocracy', either you were a Freeminer with rights to live in the Forest, or you were everyone else and could be evicted at a moment’s notice.

The turf-covered cabin, once the habitation of the Forest “cabiner,” is now almost entirely superseded by two-floored cottages, often containing not less than four apartments.

1874 A change of tune in Parliament... "one of the main difficulties arose from the rights of squatters who had been allowed to occupy property belonging to the Crown, and had thereby acquired certain interests in it. Their rights could not be lightly tampered with, but it was desirable that they should be defined more clearly than at present."

1838 Free mining rights were 'set out in law' or restated in the form of legislative 'permission' (from Parliament) rather than common law rights, up-held by customary law and traditions which cannot be arbitrarily taken away by the whims of Parliament.

1832-46 Government inquiry in the aftermath of Warren James' rebellion led to many 'squatter' settlements being legalised. Many enclosures were also opened-up. Image: Warren James' notice.

1831 Warren James at the head of the Committee of Free Miners tabled a motion that the unlawful fences be torn down. Not long after that, there were 3000 men, women and children organised into gangs, busy destroying enclosure fences, turnpikes, crown buildings and the houses of local gentry. Over a few days, Foresters had destroyed some sixty miles of fencing.

I spoke to him on the 5th, and told him in the presence of numbers the folly and danger of his proceedings; but he paid no attention, and said the Forest was given up to them in Parliament the year before; that he had a charter, which he would bring and show me. On Tuesday the 7th Mr. Ducarel and I issued a warrant to apprehend him but it could not be executed.

We swore in a number of special constables, and with the woodmen mustered about forty at the scene of action where they were to begin; but the rioters mustered nearly 200, with axes, and began their work of destruction about 7 o’clock, and we found it useless to attempt to stop them. They were soon joined by others, and supplied with cider, and continued their work Wednesday, Thursday, Friday, and Saturday. Edward Machen, Deputy Surveyor.

On the Friday, a party of 50 soldiers arrived from Monmouth, but by now the number of Foresters had grown to over 2000 and the soldiers returned to their barracks. On Sunday an infantry regiment from Plymouth arrived, by which time the Foresters were too tired for a fight -and dispersed.

1828-30 Several anti-enclosure petitions send to Parliament by the Commoners and Freeminers, the last of which was led by Warren James, a Freeminer from Parkend. All were ignored.

1814-16 Edward Machen enclosed the full 11,000 acres, as permitted by the new legislative instruments.

1813 A government report claimed that 1,111 'squatters' living in 785 houses had encroached upon (reclaimed) over 1,600 acres.

1810 Another report accused Foresters of "repeatedly destroying the new plantations (unlawful enclosures) and terrifying the adjoining districts (local authorities) by forming riotous mobs."

1808 Commoners rights infringed by the Dean Forest Timber Act which allowed 11,000 acres of woodland to be enclosed. The Dean and New Forest Act attempted to remove the Commoners' rights -an unlawful act, as Parliament has no jurisdiction over rights and customs which existed long before Parliament itself.

1795 The Government purchased huge amounts of grains and other stock from farmers, causing 'Bread Riots' across the country. Hungry Foresters got a slice of the action, by raiding farmers' wagons bound for Gloucester and ships on the Severn and distributing the foods amongst themselves. Foresters at the time were accustomed to trading coal and wood for grains and other foods from farms on the outskirts of the Forest.

1777-86 They began outlawing the Mine Law Court in 1777, and physically destroying the Mine Law documents; which constituted the laws by which the forest miners governed themselves. Soon after, outside industrialists began opening large iron and coal mines.

1712 For 200 years after the Reformation no further provision was made, indeed none was apparently required, as the Forest had been more than once nearly depopulated during that period, and was said to be almost without inhabitants in 1712.

1659-68 Forest riots "probably excited by the efforts which the Government had recently made for the re-afforesting of 18,000 acres; to effect which 400 cabins of poor people, living upon the waste, and destroying the wood and timber, were thrown down."

1639 22,000 acres were disafforested, with 4,000 going to manorial lords and freeholders in 'compensation' 18,000 acres were to go to the Crown, and be sold on to Sir John Winter. Riots ensued in 1641

1633-4 We find a proposal that "all inclosures made since James I. should be thrown back into arable on pain of forfeiture". Enclosers still prosecuted in the Star Chamber as late as 1639.

1632 Riot in defence of the commons in the Forest of Dean saw a cannon brought in from Bristol to suppress it, but the gunners refused to fire their guns.

1631 The Skimmington riots of 25 March.

1626–1632 The Western Rising was a series of riots in the Dean and other Forests against disafforestation of royal forests.

1620 Sir Edward Coke ‘greatest of English judges’, and a keen opponent of enclosure, declared depopulation against the laws of the realm ‘the encloser who kept a shepherd and dog in place of a flourishing village community was hateful to God and man.’ Ethnically cleansing ‘peasants’ is a clear violation of our ancient Common Law of Tort which is ‘cause no injury, harm or loss.’

1613 Earl of Pembroke attempted to enclose extensive areas of the Dean, In an effort to preserve their rights, the Foresters took him to the Exchequer Court and won. The ruling permitted Freeminers to continue digging for iron "out of charity and grace, not right."

1500's Foresters ancient rights first became permitted by "grace, not right", likely a means of saving face after attempts at trying to use force to prevent Foresters from commoning sheep failed, proved not worth sustained effort or unlikely to work. Even today, the Commoners rights are described as "customary rights and privileges not expressly permitted by the rule of law" which is just another way of saying, we've not managed to stop 'em yet!

1400-1409 Owain Glyndŵr last native Prince of Wales (Tywysog Cymru) viewed as a de facto King, led the ‘Welsh Revolt’ rapidly gaining control of large areas of Wales. Eventually his forces were overrun by the Normans, but despite the large rewards offered, Glyndŵr was never betrayed. His death was recorded by his kinsman in the year 1415, it is said he joined the ranks of King Arthur, and awaits the call to return and liberate his people.

1344 "With great ryot and strengthe in manner of warre," Foresters despoiled a merchant ship from Majorca sailing upon the Severn, plundering their masters and mariners and attacking those deputed to guard the goods.

1217 Charter of the Forest (Charta de Foresta) granted by 10 year old Henry III as a companion to Magna Carta confirmed the role of Verderers to oversee the 'vert and Venison' (green and game) and restated the rights of 'Freemen' to work the woodlands, collect firewood and hunt & forage for food. Rights which have been subject to a sustained and ruthless attempt at suppression ever since; but which after 800 years -Foresters still claim and use.

1140 the Abbey of Flaxley was founded by Roger, the Earl of Hereford’s eldest son, by whom it was partially endowed, and who named it “the Abbey of St. Mary de Dene”.

The Norman Genocide.

Ever since the Norman occupation, no one was permitted to live within, or even to enter the Forest. Except for Crown officials and Freeminers who had to live in villages on the edge of the Forest, often many miles from the mine workings themselves. This, of course, didn't stop many Foresters from living in the Forest their whole lives. Even in living memory seeing a troop of miners marching through the forest was commonplace.

After the Norman invasion of 1066, William 'the Bastard' declared all the land, animals and people in the whole country to be his personal property! This was as alien to the ancient Laws and Customs of the British Isle's as the colonial land-grabs were to the First Nations of America. Today, William the Bastard's 22nd Great Grand-Daughter, Queen Lizzy, is still the largest land-owner and she presides over the exact same land-monopoly that was originally established 'by Right of Conquest' in 1066.

The Normans conquered most of the Anglo-Saxon Kingdoms relatively quickly, but their rule of these Isles was far from absolute. Just like the Roman invaders they would struggle to control Wales and the borders for many centuries yet...

The ‘Greenmen’ resisted the Norman invasion. Wearing foliate camouflage, they ran guerrilla warfare campaigns against the invaders who called them the ‘silvatici’ (the men of the woods). Their leafy faces remain a symbol of defiance, and so popular were their efforts against the Norman colonisers that 'Greenmen' make an appearance in the stonework of many old chapels. The Norman invasion took us from being a country in which >90% of people owned land, to a country of landless serfs, themselves owned by foreign lords... a situation not without its parallels today!

So, we can blame the Normans for making it illegal to live in the Forest of Dean -their excuses changed throughout the centuries, first it was 'the King's land', then a ‘royal hunting ground’; more recently they called our Forest the 'national property' (King: "we need it for ships!"; Foresters: "as do we, zurry!"). Now-a-days it is referred to as the 'Public' read 'public-schoolboy' Forestry Estate (PFE) which apparently means it "belongs to everyone"... just so long as all you ever do is walk your dog or ride a bike!

The Forest before Doomsday.

Before the Normans invasion the Forest was already one of the most important iron producing districts in the British Isles. Archaeological evidence reveals that ochre has been mined here for at least 4,500 years, and our veins of iron-ore and coal were already extensively explored before the Romans arrived. It has even been suggested that Foresters may have remained 'free' from direct Roman Imperial control (perhaps as coloni or vilici) because they wanted the Freeminers to supply iron and coal.

The Silurian tribes, who led one of the most fierce and unbroken resistance campaigns against the Romans, occupied Welshbury Hill fort near Flaxley. This suggests that the Forest has always been a disputed territory, and it was more than mere 'economic convenience' which gave the Romans second thoughts.

Few people know that our modern Parish boundaries came to us from the Anglo-Saxons, and are likely even older still. In Anglo-Saxon land law or ‘folkland’ as it was called, land was held in allodial title by the group, individual ownership did occur but was limited to ensure the basic needs of the group were met. Every Parishioner had the right to collect wood, stone and other resources from the common land to build their dwelling. A home and land enough to grow your own food was seen as a right!

There is a surprising amount of continuity, in ‘open field systems’ from the fourth millennium BC up until the Norman invasion. Communal land management originated centuries, perhaps millennia before the Anglo-Saxon era. We know the Wilderness Center, Mitcheldean was originally a Saxon hunting lodge.

Like so many of the Forest's ancient rights and customs, the practice of Freemining contains traditions which likely echo-back to our pre-Christian ancestors. The Freeminers of the Dean have, since ancient times, controlled the extraction of Iron Ore and Coal and held full judicial powers in their own Mine Courts, which no 'outsiders' were even allowed to give evidence in. In late 1200's Edward I confirmed the charters and privileges of the foresters, which even then were regarded as ancient...

Bee it in minde and remembrance what ye customs and franchises hath been that were granted tyme out of minde. Any free forester might, dig for iron ore or coal where he pleased, and have right of way for carrying it.

The forest oath was taken by 'swearing upon a stick of holly,' and no stranger or professional advocate could plead in the forest courts : and none other folke to plead right, but onely the miners shall bee there, and hold a sticke of holly, and then the said myner demanding the debt shall putt his hand upon the sticke, and none others with him, and shall sweare.

Jem the Slipper

Jem the Slipper was a nineteenth century Forest of Dean cave-dwelling tanner, wild-man and purveyor of fine slippers!

He still remains a mysterious character, having lived for many years in a cave which he had dug-out and roofed with branches and sods (turfs). His wum was somewhere on the Great Doward, near Symonds Yat (sea-man's gate) but where exactly, I cussnt tael thee! In some ways Jem was one of the last of his kind, an native Forester living as his ancestors had lived for thousands of years... but, he could also have quite easily been called a pioneer of what ecologically conscious urbanites now call 'low-impact living'.

Jem the Slipper was a nineteenth century Forest of Dean cave-dwelling tanner, wild-man and purveyor of fine slippers!

He still remains a mysterious character, having lived for many years in a cave which he had dug-out and roofed with branches and sods (turfs). His wum was somewhere on the Great Doward, near Symonds Yat (sea-man's gate) but where exactly, I cussnt tael thee! In some ways Jem was one of the last of his kind, an native Forester living as his ancestors had lived for thousands of years... but, he could also have quite easily been called a pioneer of what ecologically conscious urbanites now call 'low-impact living'.

His life and livelihood were intimately linked with the Forest he loved. The Forest he both lived within, and as a part of. He was a talented hunter-gatherer, surviving mainly off what he could forage, poach and otherwise 'cadge' from his surroundings. He had no bosses, no masters and was free to spend his time and live his own life, as he saw fit. Jem also made a small living working as a tour guide and by selling rock specimens and fossils. He was a skilled, some might say 'artisan' tanner of hides and a primitive leather-worker. He became renowned for his high-quality rabbit-skin slippers, which would 'kip thee vit warmer thun a 'ot-rabbut stew!' giving him the nick-name, 'Jem the Slipper'.

Jem would no-doubt have lived a hard life, but it was one filled with a kind of freedom so few of us ever get to taste these days. His real name was James Lewis and he died in 1882, aged 86... Not 'alf bad vor a mon wot lived iz lyf owt in tha wild!

We will remember you Jem, and honour your memory!

Poems

Now this sweet vision of my boyish hours.

John Clare (1793 – 1864).

Free as Spring clouds and wild as summer flowers

is faded all – a hope that blossomed free.

And haft been once no more shall ever be.

Inclosure came and trampled on the grave

Of labour’s rights and left the poor a slave.”

The Forest now is numerous got of late,

Since moneyed men come here to speculate

Where once a little turfen hut did stand,

You’ll see a noble house and piece of land.

Kitty Drew, self-taught Forest poetess, in her poem on the Forest of Dean, (1835).

Winifred Foley

When I was a child, the Forest of Dean was remote and self-contained. We were cut off from the world-from Gloucestershire by the Severn estuary, from Monmouthshire by the River Wye; and where our northernmost hills stopped, we stopped. A 'Royal' Forest, it had been. Ten by twenty miles of secluded, hilly country; ancient woods of oak and fern; and among them small coal mines, small market towns, villages and farms. We were content to be a race apart, made up mostly of families who had lived in the Forest for generations, sharing the same handful of surnames, and speaking a dialect quite distinct from any other.

Further Reading

Into the Forest of Dean, Forestry, Commons & Clearances.

- The Forest of Dean: An Historical and Descriptive Account. H.G. Nicholls, 1858.

- Derived from personal observation, and other sources, public,

private, legendary, and local. H.G. Nicholls, the Forest's own missionary cleric takes us on a tour of the Forest, past and present from folklore to mining law, from the Silurians to the Warren James uprising.

Download in HTM format - History of Forests and Forestry in Wales up to the Formation of the Forestry Commission. William Linnard, University of Wales, 1979.

- Details on the history of forests and forestry in Wales, from the last Ice Age up to the establishment of the Forestry Commission (1919). Based on palynological and archaeological evidence, classical literature, a range of manuscript and printed sources, place-name evidence, field studies and oral testimony.

Download in PDF format - Peasant Craftsmen in the Medieval Forest. By Jean Birrell.

-

In the thirteenth century the forests still played an important role in the economy of their regions and of the country as a whole. Even the royal forests were far more than royal pleasure grounds. In many forests hundreds of local farmers, landlords, and peasants, paid agistment fees to put horses, cattle, and pigs in the forest pastures. But the forests were not only important for agriculture. A wide range of industries developed in them as a result of the presence there of basic raw materials or of ample supplies of fuel, trees and undergrowth.

Download in PDF format

- The Enclosure and redistribution of our land.

by Curtler William Henry Ricketts 1862-1925. - A history of Enclosure from the earliest until the latest times. Topics explored include changes in land law, distribution, expense of enclosing, the renting of commons, the over-whelming evidence in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries that commons did more harm than good, the exaggerated statements so often made as to the 'robbery ’ of ‘the poor’ on enclosure, the many concessions made in enclosure Acts to the small holder.

Download in PDF format - Folklore, collective memory and popular protest in seventeenth-century Forest of Dean

Dr Simon Sandall – University of Winchester. - The free miners of the Forest of Dean in Gloucestershire have long claimed that their customary mining rights were granted to them by Edward I in return for military service at the Siege of Berwick in 1296. Whatever the origin of these rights, they defined the relative autonomy of this industrial group and were regulated through the strict monopoly of the Mine Law Court. Explores the Western Rising, the legendary John Skymington, public shaming rituals and the ‘long traditions behind the foresters’ forcible defence of common rights’.

Download in PDF format - Halting and reversing enclosure in the 1630s: was Charles I the ‘Commoners King’? The Land Is Ours.

- "If the reign in its social and agrarian policy may be judged solely from the number of anti-enclosure commissions set up, then undoubtedly King Charles I is the one English monarch of outstanding importance as an agrarian reformer." – W. E. Tate

Download in HTML format

The Cabiners Association.

Kevin Cahill: Who Owns Britain?

Contact us

Get In Twtch.

Send a message to The Cabiners Association. We'd love to hear from you!

Please feel free to contact us with any questions, suggestions or concerns.

Send Us A Message

Contact Information

The Cabiners Association

The Greater Forest of Dean.

"Happy is the Eye, betwixt the Severn and the Wye."

Email Us At

General: cabiners [at} wum.land

Press: thom [at} wum.land

Call Us At

Phone: (+44) 07521 267 906

Text [best]: (+44) 07521 267 906